I have been telling people for a while that ConceptNet is a valuable source of information for semantic vectors, or “word embeddings” as they’ve been called since the neural-net people showed up in 2013 and renamed everything. Let’s call them “word vectors”, even though they can represent phrases too. The idea is to compute a vector space where similar vectors represent words or phrases with similar meanings.

In particular, I’ve been pointing to results showing that our precomputed vectors, ConceptNet Numberbatch, are the state of the art in multiple languages. Now we’ve verified this by participating in SemEval 2017 Task 2, “Multilingual and Cross-lingual Semantic Word Similarity”, and winning in a landslide.

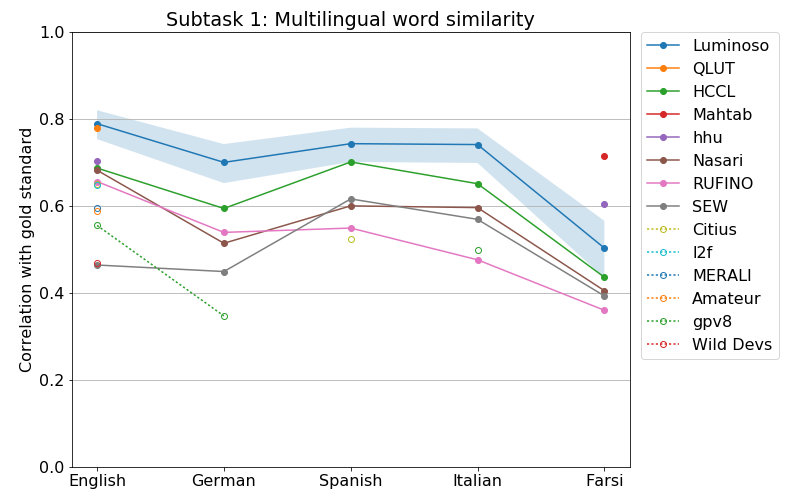

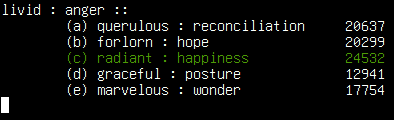

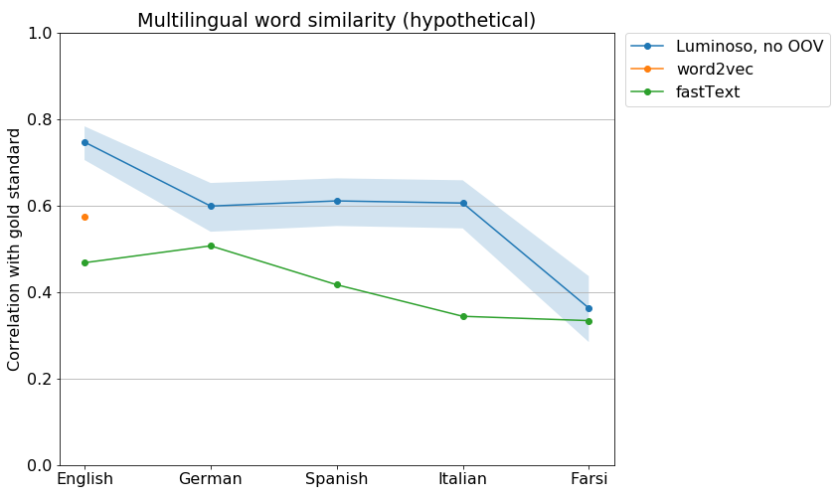

Performance of SemEval systems on the Multilingual Word Similarity task. Our system, in blue, shows its 95% confidence interval.

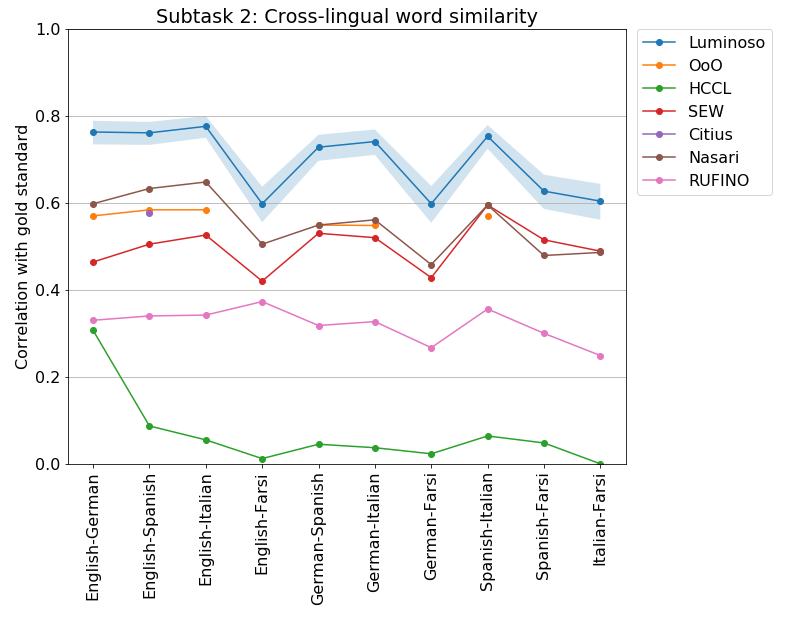

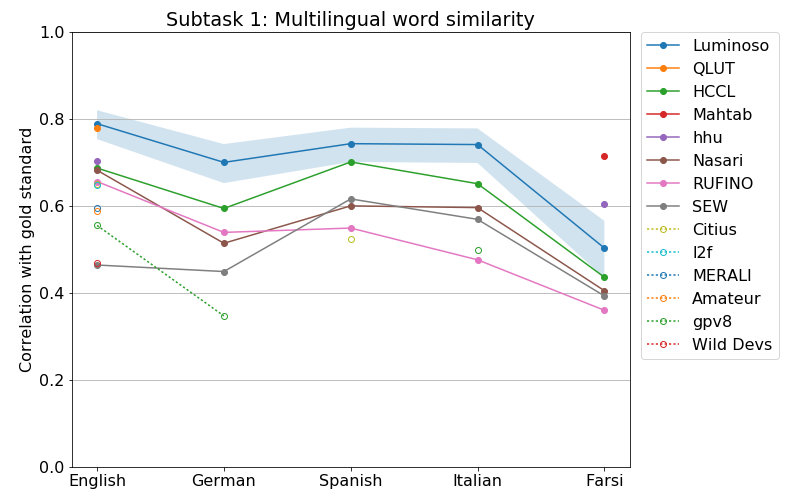

Performance of SemEval systems on the Cross-lingual Word Similarity task. Our system, in blue, shows its 95% confidence interval.

SemEval is a long-running evaluation of computational semantics. It does an important job of counteracting publication bias. Most people will only publish evaluations where their system performs well, but SemEval allows many groups to compete head-to-head on an evaluation they haven’t seen yet, with results released all at the same time. When SemEval results come out, you can see a fair comparison of everyone’s approach, with positive and negative results.

This task was a typical word-relatedness task, the same kind that we’ve been talking about in previous posts. You get a list of pairs of words, and your system has to assess how related they are, which is a useful thing to know in NLP applications such as search, text classification, and topic detection. The score is how well your system’s responses correlate with the responses that people give.

The system we submitted was not much different from the one we published and presented at AAAI 2017 and that we’ve been blogging about. It’s the product of the long-running crowd-sourcing and linked-data effort that has gone into ConceptNet, and lots of research here at Luminoso about how to make use of it.

At a high level, it’s an ensemble method that glues together multiple sources of vectors, using ConceptNet as the glue, and retrofitting (Faruqui, 2015) as the glue gun, and also building large parts of the result entirely out of the glue, a technique which worked well for me in elementary school when I had to make a diorama.

The primary goal of this SemEval task was to submit one system that performed well in multiple languages, and we did the best by far in that. Some systems only attempted one or two languages, and at least get to appear in the breakdown of the results by language. I notice that the QLUT system (I think that’s the Qilu University of Technology) is in a statistical tie with us in English, but submitted no other languages, and that two Farsi-only systems did better than us in Farsi.

On the cross-lingual results (comparing words between pairs of languages), no other system came close to us, even in Farsi, showing the advantage of ConceptNet being multilingual from the ground up.

The “baseline” system submitted by the organizers was Nasari, a knowledge-graph-based system previously published in 2016. Often the baseline system is a very simplistic technique, but this baseline was fairly sophisticated and demanding, and many systems couldn’t outperform it. The organizers, at least, believe that everyone in this field should be aware of what knowledge graphs can do, and it’s your problem if you’re not.

Don’t take “OOV” for an answer

The main thing that our SemEval system added, on top of the ConceptNet Numberbatch data you can download, is a strategy for handling out-of-vocabulary words. In the end, so many NLP evaluations come down to how you unk your OOVs. Wait, I’ll explain.

Most machine learning over text considers words as atomic units. So you end up with a particular vocabulary of words your system has learned about. The test data will almost certainly contain some words that the system hasn’t learned; those words are “Out of Vocabulary”, or “OOV”.

(There are some deep learning techniques now that go down to the character level, but they’re messier. And they still end up with a vocabulary of characters. I put the Unicode snowman ☃ into one of those systems and it segfaulted.)

Some publications use the dramatic cop-out of skipping all OOV words in their evaluation. That’s awful. Please don’t do that. I could make an NLP system whose vocabulary is the single word “chicken”, and that would get it a 100% score on some OOV-skipping evaluations, but the domain of text it could understand would be quite limited (Zongker, 2002).

In general, when a system encounters an OOV word, there has to be some strategy for dealing with it. Perhaps you replace all OOV words with a single symbol for unknown words, “unk”, a strategy common enough to have become a verb.

SemEval doesn’t let you dodge OOV words: you need to submit some similarity value for every pair, even if your system has no idea. “Unking” would not have worked very well for comparing words. It seemed to us that a good OOV strategy would make a noticeable difference in the results. We made a couple of assumptions:

- The most common OOV words are inflections or slight variations of words that are known.

- Inflections are suffixes in most of the languages we deal with, so the beginning of the word is more important than the end.

- In non-English languages, OOV words may just be borrowings from English, the modern lingua franca.

So, in cases where it doesn’t help to use our previously published OOV strategy of looking up terms in ConceptNet and replacing them with their neighbors in the graph, we added these two OOV tricks:

- Look for the word in English instead of the language it’s supposed to be in.

- Look for known words that have the longest common prefix with the unknown word.

This strategy made a difference of about 10 percent in the results. Without it, our system still would have won at the cross-lingual task, but would have narrowly lost to the HCCL system on the individual languages. But we’re handicapping ourselves here: everyone got to decide on their OOV strategy as part of the task. When the SemEval workshop happens, I’ll be interested to see what strategies other people used.

What about Google and Facebook?

When people talk about semantic vectors, they generally aren’t talking about what a bunch of small research groups came up with last month. They’re talking about the big names, particularly Google’s word2vec and Facebook’s fastText.

Everyone who makes semantic vectors loves to compare to word2vec, because everyone has heard of it, and it’s so easy to beat. This should not be surprising: NLP research did not stop in 2014, but word2vec’s development did. It’s a bit hard to use word2vec as a reference point in SemEval, because if you want non-English data in word2vec, you have to go train it yourself. I’ve done that a few times, with awful results, but I’m not sure those results are representative, because of course I’m using data I can get myself, and the most interesting thing about word2vec is that you can get the benefit of it being trained on Google’s wealth of data.

A more interesting comparison is to fastText, released by Facebook Research in 2016 as a better, faster way to learn word vectors. Tomas Mikolov, the lead author on word2vec, is now part of the fastText team.

fastText has just released pre-trained vectors in a lot of languages. It’s trained only on Wikipedia, which should be a warning sign that the data is going to have a disproportionate fascination with places where 20 people live and albums that 20 people have listened to. But this lets us compare how fastText would have done in SemEval.

The fastText software has a reasonable OOV strategy — it learns about sub-word sequences of characters, and falls back on those when it doesn’t know a word — but as far as I can tell, they didn’t release the sub-word information with their pre-trained vectors. Lacking the ability to run their OOV strategy, I turned off our own OOV strategy to make a fair comparison:

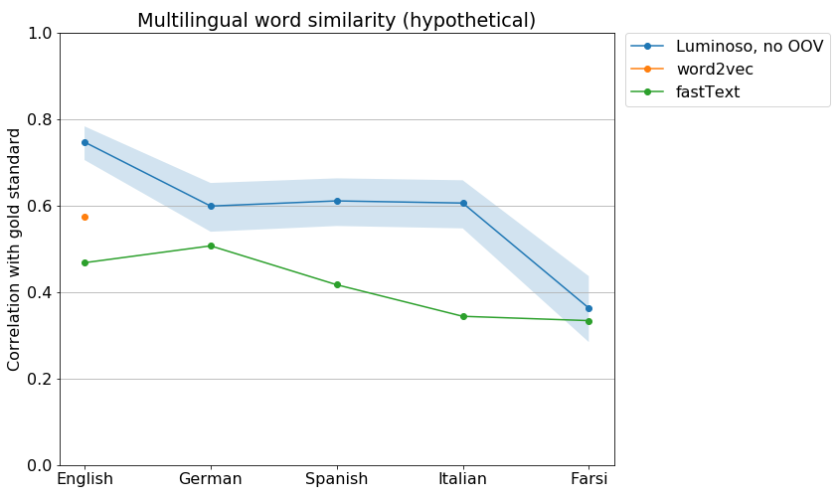

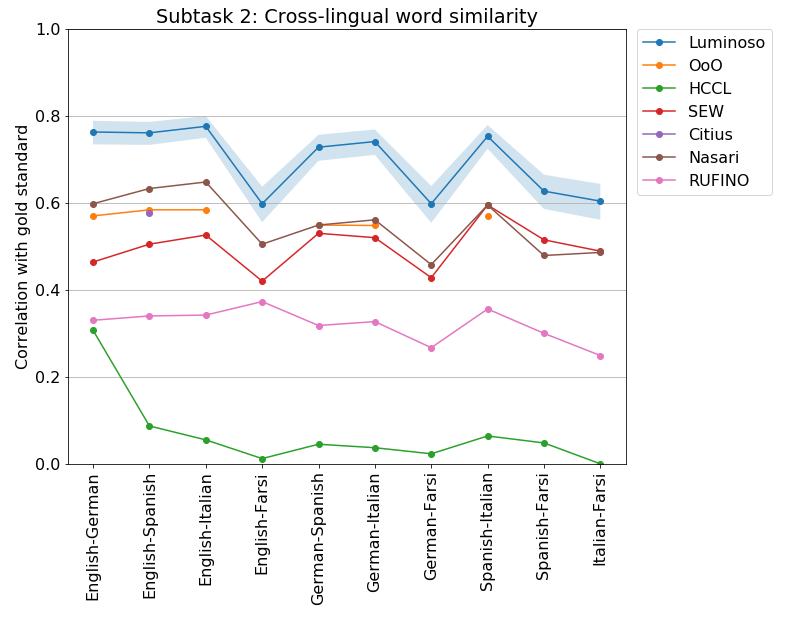

Comparison of released word vectors on the SemEval data, without using any OOV strategy.

Note that word2vec is doing better than fastText, due to being trained on more data, but it’s only in English. Luminoso’s ConceptNet-based system, even without its OOV strategy, is doing much better than these well-known systems. And when I experiment with bolting ConceptNet’s OOV onto fastText, it only gets above the baseline system in German.

Overcoming skepticism and rejection in academic publishing

Returning to trying to publish academically, after being in the startup world for four years, was an interesting and frustrating experience. I’d like to gripe about it a bit. Feel free to skip ahead if you don’t care about my gripes about publishing.

When we first started getting world-beating results, in late 2015, we figured that they would be easy to publish. After all, people compare themselves to the “state of the art” all the time, so it’s the publication industry’s job to keep people informed about the new state of the art, right?

We got rejected three times. Once without even being reviewed, because I messed up the LaTeX boilerplate and the paper had the wrong font size. Once because a reviewer was upset that we weren’t comparing to a particular system whose performance had already been superseded (I wonder if it was his). Once because we weren’t “novel” and were just a “bag of tricks” (meanwhile, the fastText paper has “Bag of Tricks” in its title). In the intervening time, dozens of papers have claimed to be the “state of the art” with numbers lower than the ones we blogged about.

I gradually learned that how the result was framed was much more important than the actual result. It makes me appreciate what my advisors did in grad school; I used to have less interesting results than this sail through the review process, and their advice on how to frame it probably played a large role.

So this time, I worked on a paper that could be summarized with “Here’s data you can use! (And here’s why it’s good)”, instead of with “Our system is better than yours! (Here’s the data)”. AAAI finally accepted that paper for their 2017 conference, where we’ve just presented it and maybe gotten a few people’s attention, particularly with the shocking news that ConceptNet still exists.

The fad-chasers of machine learning haven’t picked up on ConceptNet Numberbatch either, maybe because it doesn’t have “2vec” in the name. (My co-worker Joanna has claimed “2vec” as her hypothetical stage name as a rapper.) And, contrary to the example of systems that are better at recognizing cat pictures, Nvidia hasn’t yet added acceleration for the vector operations we use to their GPUs. (I jest. Mostly in that you wouldn’t want to do something so memory-heavy on a GPU.)

At least in the academic world, the idea that you need knowledge graphs to support text understanding is taking hold from more sources than just us. The organizers’ baseline system (Nasari) used BabelNet, a knowledge graph that looks a lot like ConceptNet except for its restrictive license. Nasari beat a lot of the other entries, but not ours.

But academia still has its own built-in skepticism that a small company can really be the world leader in vector-based semantics. The SemEval results make it pretty clear. I’ll believe that academia has really caught up when someone graphs against us instead of word2vec the next time they say “state of the art”. (And don’t forget to put error bars or a confidence interval on it!)

How do I use ConceptNet Numberbatch?

To make it as straightforward as possible:

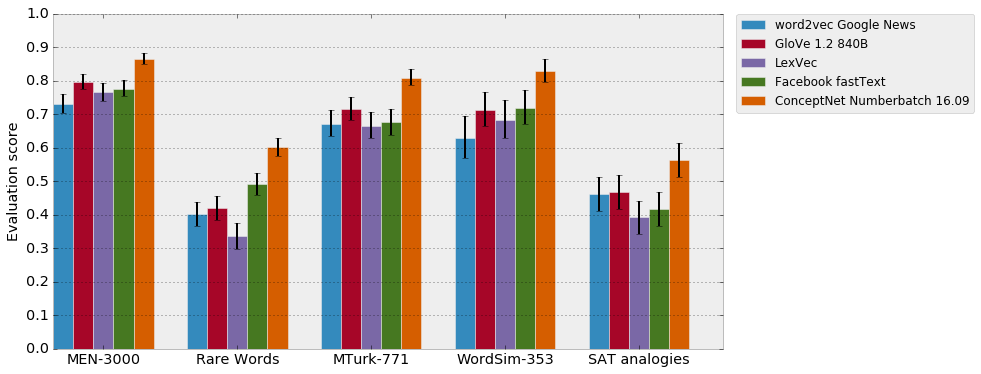

- Work through any tutorial on machine learning for NLP that uses semantic vectors.

- Get to the part where they tell you to use word2vec. (A particularly enlightened tutorial may tell you to use GloVe 1.2.)

- Get the ConceptNet Numberbatch data, and use it instead.

- Get better results that also generalize to other languages.

One task where we’ve demonstrated this ourselves is in solving analogy problems.

Whether this works out for you or not, tell us about it on the ConceptNet Gitter.

How does Luminoso use ConceptNet Numberbatch?

Luminoso provides software as a service for text understanding. Our data pipeline starts out with its “background knowledge”, which is very similar to ConceptNet Numberbatch, so that it has a good idea of what words mean before it sees a single sentence of your data. It then reads through your data and refines its understanding of what words and phrases mean based on how they’re used in your data, allowing it to accurately understand jargon, common misspellings, and domain-specific meanings of words.

If you rely entirely on “deep learning” to extract meaning from words, you need billions of words before it starts being accurate. Collecting billions of words is difficult, and the text you collect is probably not the text you really want to understand.

Luminoso starts out knowing everything that ConceptNet, word2vec, and GloVe know and works from there, so it can learn quickly from the smaller number of documents that you’re actually interested in. We package this all up in a visualization interface and an API that lets you understand what’s going on in your text quickly.

Photo credit: “The Big Red Button” by włodi, used under the CC-By-SA 2.0 license

Photo credit: “The Big Red Button” by włodi, used under the CC-By-SA 2.0 license