wordfreq 1.5: More data, more languages, more accuracy

wordfreq is a useful dataset of word frequencies in many languages, and a simple Python library that lets you look up the frequencies of words (or word-like tokens, if you want to quibble about what’s a word). Version 1.5 is now available on GitHub and PyPI.

wordfreq can rank the frequencies of nearly 400,000 English words. These are some of them.

These word frequencies don’t just come from one source; they combine many sources to take into account many different ways to use language.

Some other frequency lists just use Wikipedia because it’s easy, but then they don’t accurately represent the frequencies of words outside of an encyclopedia. The wordfreq data combines whatever data is available from Wikipedia, Google Books, Reddit, Twitter, SUBTLEX, OpenSubtitles, and the Leeds Internet Corpus. Now we’ve added one more source: as much non-English text as we could possibly find in the Common Crawl of the entire Web.

Including this data has led to some interesting changes in the new version 1.5 of wordfreq:

- We’ve got enough data to support 9 new languages: Bulgarian, Catalan, Danish, Finnish, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Norwegian Bokmål, and Romanian.

- Korean has been promoted from marginal to full support. In fact, none of the languages are “marginal” now: all 27 supported languages have at least three data sources and a tokenizer that’s prepared to handle that language.

- We changed how we rank the frequencies of words when data sources disagree. We used to use the mean of the frequencies. Now we use a weighted median.

Fixing outliers¶

Using a weighted median of word frequencies is an important change to the data. When the Twitter data source says “oh man you guys ‘rt’ is a really common word in every language”, and the other sources say “No it’s not”, the word ‘rt’ now ends up with a much lower value in the combined list because of the median.

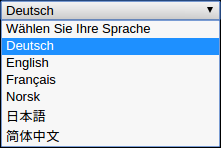

wordfreq can still analyze formal or informal writing without its top frequencies being spammed by things that are specific to one data source. This turned out to be essential when adding the Common Crawl: when text on the Web is translated into a lot of languages, there is an unreasonably high chance that it says “log in”, “this website uses cookies”, “select your language”, the name of another language, or is related to tourism, such as text about hotels and restaurants. We wanted to take advantage of the fact that we have a crawl of the multilingual Web, without making all of the data biased toward words that are overrepresented in that crawl.

The reason the median is weighted is so we can still compare frequencies of words that don’t appear in a majority of sources. If a source has never seen a word, that could just be sampling noise, so its vote of 0 for what the word’s frequency should be counts less. As a result, there are still source-specific words, just with a lower frequency than they had in wordfreq 1.4:

>>> # Some source data has split off "n't" as a separate token

>>> wordfreq.zipf_frequency("n't", 'en', 'large')

2.28

>>> wordfreq.zipf_frequency('retweet', 'en', 'large')

1.57

>>> wordfreq.zipf_frequency('eli5', 'en', 'large')

1.45

Why use only non-English data in the Common Crawl?¶

Mostly to keep the amount of data manageable. While the final wordfreq lists are compressed down to kilobytes or megabytes, building these lists already requires storing and working with a lot of input.

There are terabytes of data in the Common Crawl, and while that’s not quite “big data” because it fits on a hard disk and a desktop computer can iterate through it with no problem, counting every English word in the Common Crawl would involve intermediate results that start to push the “fits on a hard disk” limit. English is doing fine because it has its own large sources, such as Google Books.

More data in more languages¶

A language can be represented in wordfreq when there are 3 large enough, free enough, independent sources of data for it. If there are at least 5 sources, then we also build a “large” list, containing lower-frequency words at the cost of more memory.

There are now 27 languages that make the cut. There perhaps should have been 30: the only reason Czech, Slovak, and Vietnamese aren’t included is that I neglected to download their Wikipedias before counting up data sources. Those languages should be coming soon.

Here’s another chart showing the frequencies of miscellaneous words, this time in all the languages:

Getting wordfreq in your Python environment is as easy as pip install wordfreq. We hope you find this data useful in helping computers make sense of language!

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus