ConceptNet Numberbatch 17.04: better, less-stereotyped word vectors

Word embeddings or word vectors are a way for computers to understand what words mean in text written by people. The goal is to represent words as lists of numbers, where small changes to the numbers represent small changes to the meaning of the word. This is a technique that helps in building AI algorithms for natural language understanding — using word vectors, the algorithm can compare words by what they mean, not just by how they’re spelled.

But the news that’s breaking everywhere about word vectors is that they also represent the worst parts of what people mean. Stereotypes and prejudices are baked into what the computer believes to be the meanings of words. To put it bluntly, the computer learns to be sexist and racist, because it learns from what people say.

There are many articles you could read for background on the problem, including:

- Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases, by Aylin Caliskan, Joanna J. Bryson, and Arvind Narayanan, published in Science

- Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing word embeddings, by Tolga Bolukbasi et al., working with Microsoft Research

- Scientists Taught A Robot Language. It Immediately Turned Racist., written by Nidhi Subbaraman for that paragon of science reporting, BuzzFeed

We want to avoid letting computers be awful to people just because people are awful to people. We want to provide word vectors that are not just the technical best, but also morally good. So we’re releasing a new version of ConceptNet Numberbatch that has been post-processed to counteract several kinds of biases and stereotypes.

If you use word vectors in your machine learning and the state-of-the-art accuracy of ConceptNet Numberbatch hasn’t convinced you to switch from word2vec or GloVe, we hope that built-in de-biasing makes a compelling case. Machine learning is better when your machine is less prone to learning to be a jerk.

How do we evaluate that we’ve made ConceptNet Numberbatch less prejudiced than competing systems? There seem to be no standardized evaluations for this yet. But we’ve created some evaluations based on the data from these recent papers. We’re making it a part of the ConceptNet build process to automatically de-bias Numberbatch and evaluate how successful that de-biasing was.

The Bolukbasi et al. paper describes how to counteract gender bias, and by adapting the techniques of that paper, we can reduce the gender bias we observe to almost nothing. Biases regarding race, ethnicity, and religion are harder to define, and therefore harder to remove, but it’s important to make progress on this anyway.

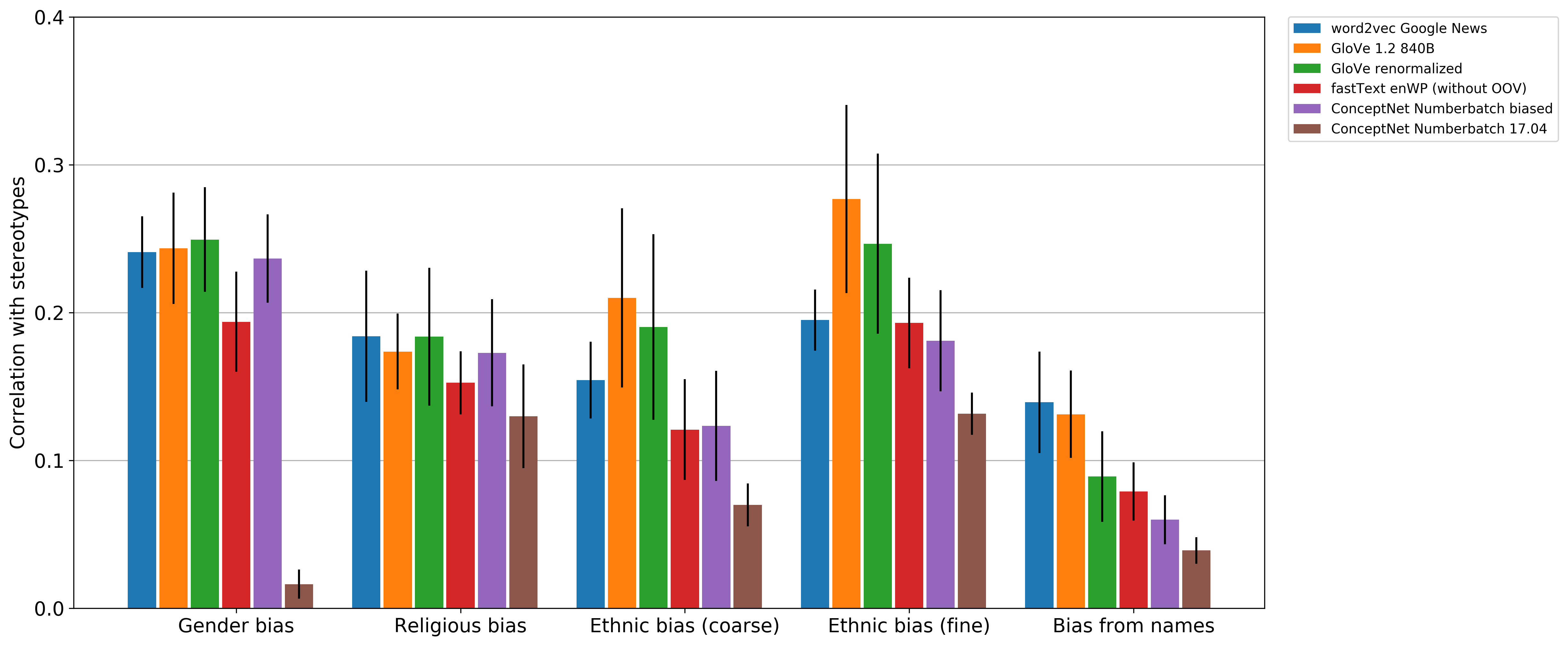

The graph you see below shows what we’ve done so far. The y-axis is a scale that we came up with involving the dot products between word vectors and their possible stereotypes: closer to zero is better. The brown bar, “ConceptNet Numberbatch 17.04”, is the de-biased system we’re releasing. (The version number represents the date, April 2017.)

We’re not trying to say we’ve solved the problem, but we can conclude that we’ve made the problem smaller. Keep in mind that this evaluation itself will likely change in the future, as we gain a better understanding of how to measure bias.

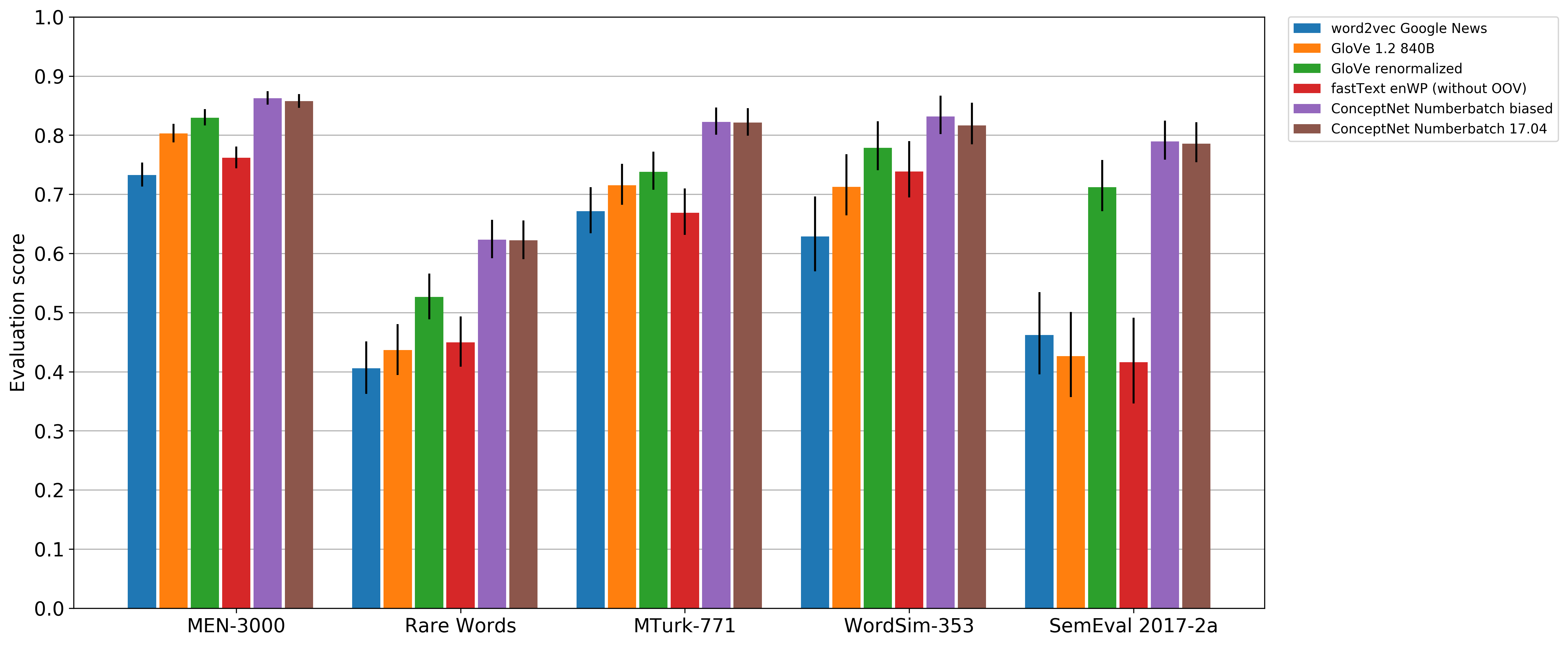

In dealing with machine-learning bias, there’s the concern that removing the bias could also cause changes that remove accuracy. But we’ve found that the change is negligible: about 1% of the overall result, much smaller than the error bars. Here’s the updated evaluation graph. The y-axis is the Spearman correlation with gold standard data (higher is better). The evaluations here are for English words only — Numberbatch covers many more languages, but the systems we’re comparing to don’t.

ConceptNet Numberbatch is already so much more accurate than any other released system that it can lose 1% of its accuracy for a good cause. If you want 1% more accuracy out of your word vectors, I suggest focusing on improving a knowledge graph, not putting back the stereotypes.

Systems we compare to¶

In the graphs above, “word2vec Google News” is the popular system from 2013-2014 that many people go to when they think “oh hey I need some word vectors”. Its continued relevance is largely due to the fact that it lets you use data that’s learned from Google’s large corpus of news, a very nice corpus which you can’t actually have. We use its results as an input to ConceptNet Numberbatch.

“GloVe 1.2 840B” is a system from Stanford that is better in some cases, and learns from reading the whole Web via the Common Crawl. It seems to have some fixable problems with the scaling of its features. “GloVe renormalized” is Luminoso’s improvement on GloVe, which we also use as an input.

“fastText enWP (without OOV)” is Facebook’s word vectors trained on the English Wikipedia, with the disclaimer that their accuracy should be better than what we show here. Facebook’s fastText comes with a strategy for handling out-of-vocabulary words, like Numberbatch does. But the data they make available for applying that strategy is in an undocumented binary format that I haven’t deciphered yet.

Gender analogies and gender bias¶

The word2vec authors (Tomas Mikolov et al.) showed that there was structure in the meanings of the vectors that word2vec learned, allowing you to do arithmetic with word meanings. If you’ve read anything about word vectors before, you’re probably tired of this example by now, but it will make a good illustration: you can take the vector for the word “king”, then subtract “man” and add “woman” to it, and the result is close to the vector for the word “queen”.

Let’s de-mystify how that happens a bit. Word2vec has read many billions of words (in particular, words in articles on Google News) and learned about what contexts they appear in. The operation “king - man + woman” is essentially asking to find a word that’s used similarly to the word “king”, but one whose context is more like the word “woman” than the word “man”. For example, a word that’s like “king” but appears with the words “she” and “her”. The clear answer is “queen”.

So the vectors learned by word2vec (and many later systems) can express analogy problems as mathematical equations:

woman - man ≈ queen - king

This is remarkably similar to the way that analogies are presented in, for example, an English class, or a standardized test such as the Miller Analogies Test or former SAT tests:

woman : man :: queen : king

Evaluating analogies like these led researchers to wonder what other analogies could be created in this system by adding “woman” and subtracting “man” to a word, or vice versa. And some of the results revealed a problem.

In the following examples, the word2vec system was given the first three words of an analogy, and asked for the word in its vocabulary that best completed the equation. The results revealed gender biases that had been baked into the system:

man : woman :: shopkeeper : housewife

man : woman :: carpentry : sewing

man : woman :: pharmaceuticals : cosmetics

I wonder if the excessive focus on Mikolov et al.’s analogy evaluation has exacerbated the problem. When a system is asked repeatedly to make analogies of the form male word : female word :: other male word : other female word, and it’s evaluated on this and its knowledge of geography and not much else, is it any surprise that we end up with systems that amplify stereotypes that distinguish women and men?

The problem is not just a theoretical problem that shows up when playing with analogies. Word embeddings are actively used in many different fields of natural language processing. A system that searches résumés for people with particular programming skills could end up ranking women lower: the phrase “she developed software for…” would be a worse match for the classifier’s expectations than “he developed software for…”.

This is one of the biases that we strive to remove, and the one we are most successful at removing, as described later in this post.

Word embeddings contain ethnic biases, too¶

The work on understanding and removing gender biases has been published for a while. But while working on this, I noticed that the data also contained significant racial and ethnic biases, which it seemed nobody was talking about. Just recently, the Caliskan et al. article came out and provided some needed illumination on the issue.

I had tried building an algorithm for sentiment analysis based on word embeddings — evaluating how much people like certain things based on what they say about them. When I applied it to restaurant reviews, I found it was ranking Mexican restaurants lower. The reason was not reflected in the star ratings or actual text of the reviews. It’s not that people don’t like Mexican food. The reason was that the system had learned the word “Mexican” from reading the Web.

If a restaurant were described as doing something “illegal”, that would be a pretty negative statement about the restaurant, right? But the Web contains lots of text where people use the word “Mexican” disproportionately along with the word “illegal”, particularly to associate “Mexican immigrants” with “illegal immigrants”. The system ends up learning that “Mexican” means something similar to “illegal”, and so it must mean something bad.

The tests I implemented for ethnic bias are to take a list of words, such as “white”, “black”, “Asian”, and “Hispanic”, and find which one has the strongest correlation with each of a list of positive and negative words, such as “cheap”, “criminal”, “elegant”, and “genius”. I did this again with a fine-grained version that lists hundreds of words for ethnicities and nationalities, and thus is more difficult to get a low score on, and again with what may be the trickiest test of all, comparing words for different religions and spiritual beliefs.

In these tests, for each positive and negative word, I find the group-of-people word that it’s most strongly associated with, and compare that to the average. The difference is the bias for that word, and in the end it’s averaged over all the positive and negative words. This appears in the graphs as “Ethnic bias (coarse)”, “Ethnic bias (fine)”, and “Religious bias”.

Note that it’s infeasible to reach 0 on this scale — words for groups of people will necessarily have some different associations. Even random differences between the words would give non-zero results. This is one reason I don’t consider the scale to be final. I’d like to make one that works like the gender-bias scale, where reaching 0 is attainable and desirable.

The Science article uncovers racial biases in a different way: it looks for different associations with predominantly-black names, such as “Deion”, “Jamel”, “Shereen”, and “Latisha”, versus predominantly-white names, such as “Amanda”, “Courtney”, “Adam”, and “Harry”. I incorporated a version of this (and also added some predominantly Hispanic and Islamic names) as another test, shown on the graph as “Bias from names”.

In ConceptNet Numberbatch, we’ve extended Bolukbasi’s de-biasing method to cover multiple types of prejudices, including ethnic and religious. This, too, is discussed below in the “What we’ve done” section.

Porn biases¶

While we’re talking about the biases that an algorithm gets from reading the Web, let’s talk about another large influence: a lot of the Web is porn.

A system that reads the text of pages sampled from the Web is going to read a lot of the text of porn pages. As such, it is going to end up learning associations for many kinds of words, such as “girlfriend”, “teen”, and “Asian”, that would be very inappropriate to put into production in a machine learning system.

Many of these associated terms, such as “slut”, are negative in connotation. This causes gender bias, ethnic bias, and more. When countering all of these biases, we need to make sure that people are not associated with degrading terminology because of their gender, ethnicity, age, or sexual orientation. This is another aspect of words that we strive to de-bias.

How to fix machine-learning biases¶

Biases and prejudices are clearly a big problem in machine learning, and at least some machine learning researchers are doing something about it. I’ve seen two major approaches to fixing biases, and as a shorthand, I’ll call them “Google-style” and “Microsoft-style” fixes, though I’m aware that these are just one project from each company and probably don’t represent a company-wide plan. The main difference is at what stage of the process you try to remove biases.

What I call “Google-style” de-biasing is described in a post on the Google Research Blog, “Equality of Opportunity in Machine Learning”. In this view, the data is what it is; if the data is unfair, it’s a reflection of the world being unfair. So the goal is to identify the point at which a machine learning tool makes a decision that affects someone (their example is a classifier that decides whether to grant a loan), and de-bias the actual decision that it makes, providing equal opportunity regardless of what the system learned from its data.

They caution against “fairness through unawareness”, the attempt to produce a system that’s unbiased just because it’s not told about attributes such as gender or race, because machine learning is great at picking up on correlated patterns that could be a proxy for gender or race.

Google’s approach is a principled and reasonable approach to take, especially in a workplace that venerates data above all else. But it sounds like it involves a large and never-ending amount of programmer effort to ensure that biased data leads to unbiased decisions. I have to wonder how many of Google’s products that use machine learning really have a working “equal opportunity filter” on their output.

In the “Microsoft-style” approach, when your data is biased against some group of people, you change the data until it’s more fair, which should help to de-bias anything you do with that data. This approach avoids “unawareness” because it adjusts all the data that’s correlated with the identified bias. I call this “Microsoft-style” because it’s based on the Microsoft Research paper (Bolukbasi et al.) that I linked to.

To remove a gender bias from word embeddings, for example, you can collect many examples of word pairs that are gender-biased and shouldn’t be (such as “doctor” vs. “nurse”), and use them to find the combination of word-embedding components that are responsible for gender bias. Then you mathematically adjust the components so that that combination comes out to 0.

It’s not quite that simple — doing exactly what I said could result in a system that’s unbiased because it has no idea what gender is, which would harm its ability to understand words that carry actual information about gender (such as “she” or “uncle”). You need to also have examples of words that are appropriate to distinguish by gender, such as “he” and “she”, or “aunt” and “uncle”. You then train the system to find the right balance between destroying biased assumptions and preserving useful information about gender.

To summarize the effects of these approaches, I would say that Microsoft-style de-biasing is more transferable between different tasks, but Google-style lets you positively demonstrate that certain things about your system are fair, if you use it consistently. If you control your machine learning pipeline from end to end, from source data to the point where you make a decision, I would say you should do both.

What we’ve done¶

In the new release of ConceptNet Numberbatch, we adapt one of the “Microsoft-style” techniques from Bolukbasi et al., but we remove many types of biases, not just one.

The process goes like this:

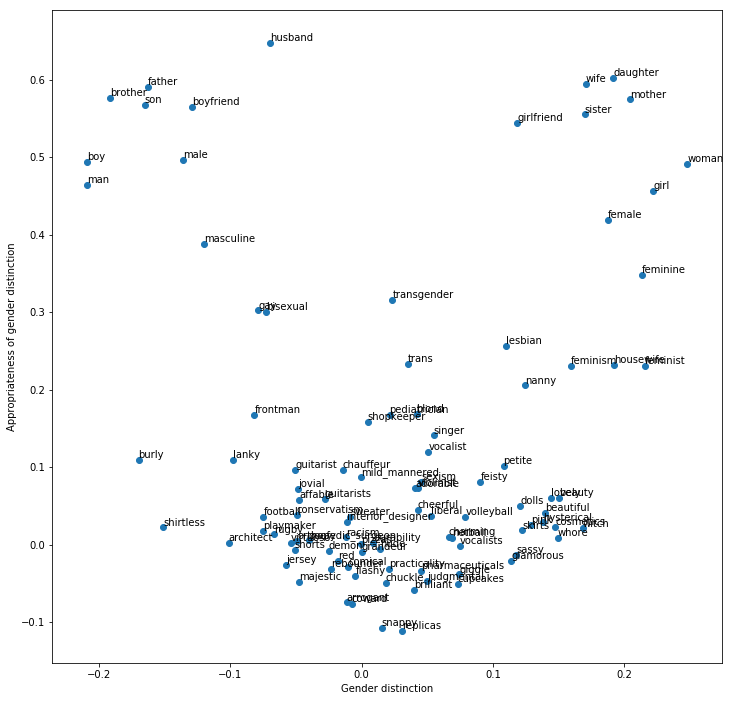

- Classify words according to the appropriateness of a distinction. For example, “mother” vs. “father” contains an appropriate gender distinction that we shouldn’t change. “Homemaker” vs. “programmer” contains an inappropriate distinction. Bolukbasi provided some nice crowd-sourced data about what people consider appropriate.

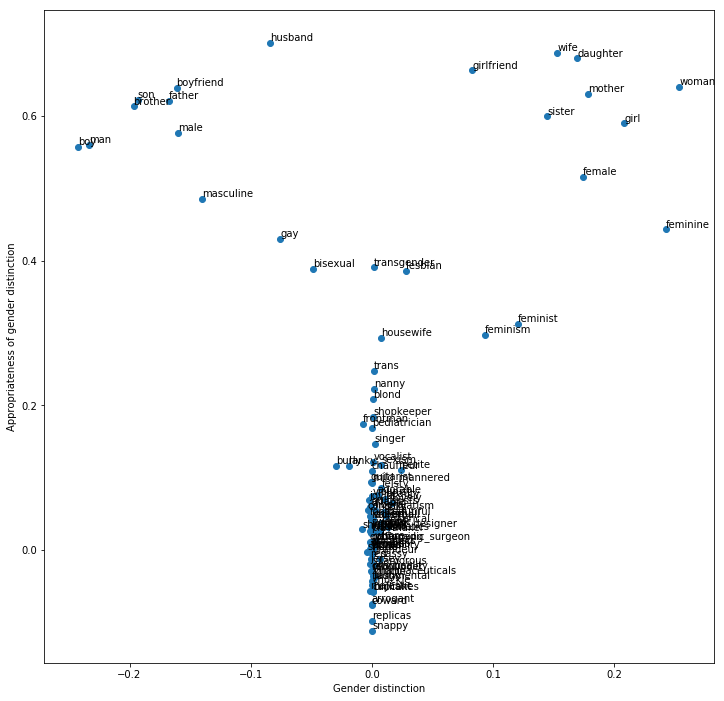

- Adjust the word vectors for words on the “inappropriate” side algebraically, so that the distinction they shouldn’t be making comes out to zero.

- Evaluate how successful we were at removing the bias, by testing it on a different set of words than the ones we used to find the bias.

The graph below shows the gender bias that we aim to remove. Words are plotted according to how much they’re associated with male words (on the left) or female words (on the right), and according to whether our classifier says this association is appropriate (on the top) or inappropriate (on the bottom).

And here’s what the graph looks like after de-biasing. The inappropriate gender distinctions have been set to nearly zero.

We use similar steps to remove biased associations with different races, ethnicities, and religions. Because we don’t have nice crowd-sourced data for exactly what should be removed in those cases, we instead aim to de-correlate them with words representing positive and negative sentiment.

We hope we’re pushing word vectors away from biases and prejudices, and toward systems that don’t think of you any differently whether you’re named Stephanie or Shanice or Santiago or Syed.

Using the results¶

ConceptNet Numberbatch 17.04 is out now, with the vectors available for research into text understanding and classification. The format is designed so they can be used as a replacement for word2vec vectors.

In Luminoso products, we use a version of ConceptNet Numberbatch that’s adapted to our text-understanding pipeline as a starting point, providing general background knowledge about what words mean. Numberbatch represents what Luminoso knows before it learns about your domain, and allows it to quickly learn to understand words from a particular domain because it doesn’t have to learn an entire language from scratch.

Our next practical step is to incorporate the newest Numberbatch into Luminoso, with both the SemEval accuracy improvements and the de-biasing.

In further research, we aim to refine how we measure these different kinds of biases. One improvement would be to measure biases in languages besides English. Numberbatch vectors are aligned across different languages, so the de-biasing we performed should affect all languages, but it will be important to test this with some multilingual data.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus