Conceptnet Numberbatch: a new name for the best word embeddings you can download

Recently at Luminoso, we’ve been promoting one of the open-source, open-data products of our research: a set of semantic vectors that we made by combining ConceptNet with other data sources. As I’m launching this new ConceptNet blog, it’s a good time to promote it some more, as it shows why the knowledge in ConceptNet is more important than ever.

Semantic vectors (also known as word embeddings from a deep-learning perspective) let you compare word meanings numerically. Our vectors are measurably better for this than the well-known word2vec vectors (the ones you download from the archived word2vec project page that are trained on Google News), and it’s also measurably better than the GloVe vectors.

To be fair, this system takes word2vec and GloVe as inputs so that it can improve them. One great thing about vector representations is that you can put them together into an ensemble that’s better than its parts.

The name that we gave it when writing a paper about the system is quite a mouthful. The “ConceptNet Vector Ensemble”. I found myself stumbling over the name when giving updates on it at meetings, while trying to get people to not shorten it to “ConceptNet”, which is a much broader project. It’s hard to get this to catch on as an improvement over word2vec if it has such an anti-catchy name.

Last week, Google released an English parsing model named “Parsey McParseface”. Everybody has heard about it. Giving your machine-learning model a silly Internetty name seems to be a great idea.

And that’s why the ConceptNet Vector Ensemble is now named Conceptnet Numberbatch.

It even remains an accurate, descriptive name! I bet Google’s parser doesn’t even have a face.

What does Conceptnet Numberbatch do?¶

Conceptnet Numberbatch is a set of semantic vectors: it associates words and phrases in a variety of languages with lists of 600 numbers, representing the gist of what they mean.

Some of the information that these vectors represent comes from ConceptNet, a semantic network of knowledge about word meanings. ConceptNet is collected from a combination of expert-created resources, crowdsourcing, and games with a purpose.

If you want to apply machine learning to the meanings of words and sentences, you probably want your system to start out knowing what a lot of words mean. By comparing semantic vectors, you can find search results that are “near misses” that don’t exactly match the search term, you can tell when one sentence is a paraphrase of another sentence, and you can discover the general topics that are being talked about by finding clusters of vectors.

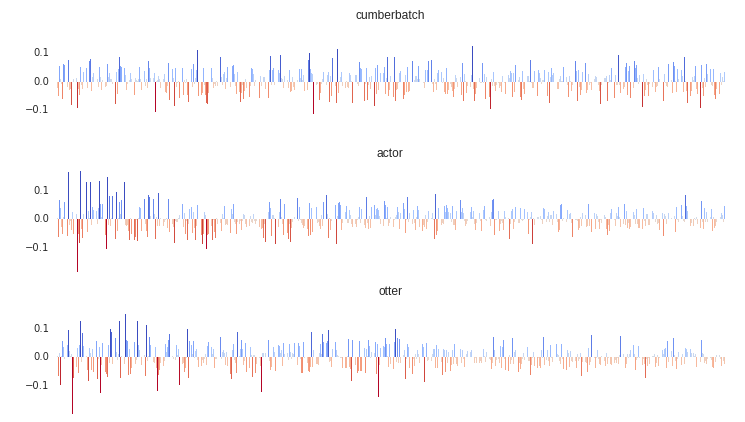

Here’s an example that we can step through. Suppose we want to ask Conceptnet Numberbatch whether Benedict Cumberbatch is more like an actor or an otter. We start by looking up the rows labeled cumberbatch, actor, and otter in Numberbatch. This gives us a 600-dimensional unit vector for each of them. Here are all of them graphed component-by-component:

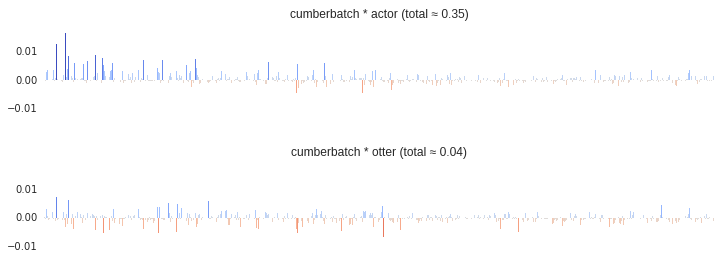

These are pretty hard for us to compare visually, but arrays of numbers are quite easy for computers to work with. The important thing here is that vectors that are similar will point in similar directions (which means they have a high dot product as unit vectors). When we look at them component-by-component here, that means that a vector is similar to another vector when they are positive in the same places and negative in the same places. We can visualize this similarity by multiplying the vectors component-wise:

The cumberbatch * actor plot shows a lot more positive components and fewer negative components than cumberbatch * otter, particularly near the left side. The term cumberbatch is like actor in many ways, and unlike it in very few ways. Adding up the component-wise products, we find that cumberbatch is 0.35 similar to actor on a scale from -1 to 1, and it’s only 0.04 similar to otter.

Another way to understand these vectors is to rank the semantic vectors that are most similar to them. Here are examples for the three vectors we looked at:

otter¶

/c/en/otter 1.000000 /c/en/japanese_river_otter 0.993316 /c/en/european_otter 0.988882 /c/en/otterless 0.951721 /c/en/water_mammal 0.938959 /c/en/otterlike 0.872185 /c/en/otterish 0.869584 /c/en/lutrine 0.838774 /c/en/otterskin 0.833183 /c/en/waitoreke 0.694700 /c/en/musteline_mammal 0.680890 /c/en/raccoon_dog 0.608738

actor¶

/c/en/actor 1.000001 /c/en/role_player 0.999875 /c/en/star_in_film 0.950550 /c/en/actorial 0.900689 /c/en/actorish 0.866238 /c/en/work_in_theater 0.853726 /c/en/star_in_movie 0.844339 /c/en/stage_actor 0.842363 /c/en/kiruna_stamell 0.813768 /c/en/actress 0.798980 /c/en/method_act 0.777413 /c/en/in_film 0.770334

cumberbatch¶

/c/en/cumberbatch 1.000000 /c/en/cumbermania 0.871606 /c/en/cumberbabe 0.853023 /c/en/cumberfan 0.837851 /c/en/sherlock 0.379741 /c/en/star_in_film 0.373129 /c/en/actor 0.367241 /c/en/role_player 0.367171 /c/en/hiddlestoner 0.355940 /c/en/hiddleston 0.346617 /c/en/actorfic 0.344154 /c/en/holmes 0.337961

We evaluated Numberbatch on several measures of semantic similarity. A system scores highly on these tests when it makes the same judgments about which words are similar to each other that a human would. Across the board, Numberbatch is the system with the most human-like similarity judgments. The code and data that support this are available on GitHub.

How does this fit into ConceptNet in general?¶

ConceptNet is a semantic network of knowledge about word meanings. Since 2007, long before anyone called these “word embeddings”, we’ve provided vector representations of the terms in ConceptNet that can be compared for similarity. We used to make these by decomposing the link structure of ConceptNet using SVD. Now, a variation on Faruqui et al.’s retrofitting does the job better, and that’s what Numberbatch does.

The current version of Numberbatch, 16.04, uses a transformed version of ConceptNet 5.4. It’s not available through the ConceptNet API — for now, you download Numberbatch separately from its own GitHub page.

ConceptNet 5.5 is going to arrive soon, and a new version of Numberbatch based on that data will be merged into its codebase.

Wait, why did the N become lowercase?¶

You sure ask the important questions, hypothetical reader. Keeping the N in ConceptNet capitalized would be more consistent, but it’d break the flow. You’d probably read “ConceptNet Numberbatch” in a way that sounds less like a double-dactyl name than “Conceptnet Numberbatch” does.

Capitalize the N if you want. Lowercase all the letters if you want. The orthography of these project names isn’t sacred anyway. ConceptNet itself originated from a project that could be called “OpenMind Commonsense”, “OpenMind CommonSense”, “Open Mind Commonsense”, or various other variations until we let it settle on four normal words, “Open Mind Common Sense”. (OMCS was named in the ‘90s. Give everyone involved a break.)

Please explain the name and why otters are involved¶

There’s a fine Internet tradition of concocting names that sound very approximately like “Benedict Cumberbatch”, and now we’ve adopted one such name for our research. For more details, you should read A Linguist Explains the Rules of Summoning Benedict Cumberbatch on The Toast. Then, if you manage to come back from there, you should gaze upon Red Scharlach’s Otters Who Look Like Benedict Cumberbatch.

Conceptnet Numberbatch is entirely our own choice of name, and should not indicate affiliation with or endorsement by any person or any otter.

Coincidentally, back in the day, ConceptNet 3 was partly developed on a PowerMac named “otter”.

The particular otter at the top of this post was photographed by Bernard Landgraf, who has taken several excellent nature photos for Wikipedia. The photo is freely available under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license.

No otters were harmed in the production of this research.

Comments

Comments powered by Disqus